30 October 2016

The Big 5 Publishers

The "Big Five" is an industry nickname for the 5 large companies that own just about every publishing imprint in the United States. It used to be "The Big Six", but Random House and Penguin recently merged creating 'Penguin Random House'. So, even though as an illustrator you may aspire to someday work for Tor Books, you are technically working for MacMillan Publishing.

Not coincidentally, every one of the Big Five book publishers are based in New York City.

Recently, writer and data scientist, Ali Almossawi, compiled a chart of all the Publishers, and every one of their subsidiaries.

This chart is a wonderful opportunity for artists wanting to promote their work in the book market. Just think, nearly every one of these imprints has an Art Director with a need to hire a professional artist.

Charles-François Daubigny

Contrary to the notion you might get from some sources, French Impressionism did not spring full-blown from the brushes of Monet, Renoir, Sisley and Bazille the moment they met in Charles Gleyre’s atelier in the 1860’s.

Not only did the fully realized style we know as Impressionism take time to develop among the artists themselves, the fundamentals on which it is based can be traced back through a logical progression from preceding artists and movements.

Chief among them were the painters of the Barbizon School, French painters who were inspired by the true-to-nature location painting of John Constable in the early 19th century, the Realism of Gustave Courbet and the direct observation and rendering of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, and who came to Barbizon and the neighboring Forest of Fontainebleau to paint in the 1820s.

You can see in the work of all of these painters, as well as in the paintings of Manet, Boudin and others, the elements that would make up the techniques of Impressionism — painting from nature, the pursuit of the effects of light, the short, separate painterly, brush marks, wet on wet paint application and the direct approach to painting, rather than the careful layers of glazing favored by academic painting of the time.

A new exhibition organized by the Taft Museum of Art in Cincinnati, the National Galleries of Scotland and the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam attempts to bring one Barbizon painter forward in particular as a progenitor of Impressionism.

Daubigny, Monet, Van Gogh: Impressions of Landscape is an exhibition currently at the Van Gogh museum — after a run at the other two — that focuses on the influence of French painter Charles-François Daubigny on Monet and the other Impressionists, as well as on Post-Impressionists like Van Gogh.

There is a nice article on The Culture Trip that describes the exhibition and gives some background on the painters and their relationships.

Daubigny (pronounced “doh-bee-nee”) trained at the French Academy and initially painted in the formal style favored by that influential institution, using location sketches for reference to compose idealized studio works. In the early 1840s he moved to Barbizon in the French countryside and began to paint directly from nature.

I’m not certain how the influences moved between Daubigny and the other Barbizon painters like Théodore Rousseau and Jean-François Millet, but I know that Daubigny became an influential member of the circle, even though he was younger than most of the other painters there.

Following paths blazed by role models and mentors like Constable, Corot and Courbet, the painters in Barbizon took landscape painting a long way from the formalism of the Academy to the fresh, lively, painted-from-nature works that would so influence the Impressionists.

The Daubigny painting above, top (with detail) was painted in 1857, a year before the earliest known painting by Monet (which was much more traditional in approach than his later Impressionist work).

Daubigny met Monet in London in the mid-1860s, and they painted together in the Netherlands. Monet even started painting from a boat, a practice that Daubigny had initiated during his time in Barbizon.

The exhibition, and the book that accompanies it, Inspiring Impressionism: Daubigny, Monet, Van Gogh, go on to explore further Daubigny’s influence on the development of Impressionism, and on the course of landscape painting in general.

In the meanwhile, I’ve gathered some links and resources to explore Daubigny’s work.

Writer Émile Zola, in his comments on Daubigny’s paintings on display at the Paris World’s Fair in 1878, wrote: “Look at any landscape by Daubigny: it is the very soul of nature that speaks to you.”

26 October 2016

25 October 2016

23 October 2016

21 October 2016

20 October 2016

18 October 2016

16 October 2016

Raymond Chandler on Character

I often talk about how creating distinct and interesting characters with unique personalities is one of the most important parts of our trade. I'm warning you now, this is another one of those posts!

Raymond Chandler was a writer of detective novels and the creator of the iconic hard boiled detective Philip Marlowe. Towards the end of his career, he sat down for an interview with Ian Fleming, the writer of the James Bond novels.

If you Google something like "Raymond Chandler Ian Fleming interviews", you'll be able to find transcriptions and youtube excerpts so you can read it, or listen to it, or both. The entire thing is in a SoundCloud file that can be heard here.

Here's the passage that I thought was the most interesting and relevant to this particular topic:

Ian Fleming: I wonder what the basic ingredients of a good thriller really are. Of course, you should have pace; it should start on the first page and carry you straight through. And I think you've got to have violence, I think you've got to have a certain amount of sex, you've got to have a basic plot, people have got to want to know what's going to happen by the end of it.

Raymond Chandler: Yes, I agree. There has to be an element of mystery, in fact there has to be a mysterious situation. The detective doesn't know what it's all about, he knows that there's something strange about it, but he doesn't know just what it's all about. It seems to me that the real mystery is not who killed Sir John in his study, but what the situation really was, what the people were after, what sort of people they were.

Ian Fleming: That's exactly what you write about, of course - you develop your characters very much more than I do, and the thriller element it seems to me in your books is in the people, the character building, and to a considerable extent in the dialogue, which of course I think is some of the finest dialogue written in any prose today.

The part I found the most interesting was this one:

It seems to me that the real mystery is not who killed Sir John in his study, but what the situation really was, what the people were after, what sort of people they were.

Characters are important because they're our avatars in the movie. The way we watch movies is by relating to the characters and projecting ourselves onto them and experiencing the stories through their shoes. So as Chandler is saying here, I think the most important aspect of any story is who the characters are, what they want, and why they are doing what they are doing.

I've seen articles online where people talk about stories like "Harry Potter", "Lord of the Rings" or "Game of Thrones", and these articles tend to focus on what wonderful worlds those authors have created. People marvel at the imagination of J. K. Rowling and how she's thought through every nuance of the world that Harry Potter lives in.

That's undoubtable true, but it's not why those stories speak to people, in my opinion. I think Rowling is actually really good at writing characters that we can relate to. Her characters are so wonderfully universal and yet feel specific and not at all generic. We've all met the kinds of students she describes when we were in school. We've all had teachers like the ones she describes. They may be wizards but they are full of real human qualities, both good and bad. They're very rich characters. And Rowling does a really good job of always letting us know why they're doing what they're doing. Some are motivated by greed, some by fear, some by good intentions, some by guilt, etc.

As Chandler says, in Rowling's stories we always know "what the people were after". Knowing what drives a character and how far they will go to get what they want is as much a part of their personality as anything else. We're all driven by different wants and needs at different times and we can relate to characters who are driven by similar wants and needs. Once we can relate to characters, then you can really get an audience to feel empathy for a character and worry about them, or feel full of dread for them, or feel sorry for them or feel happy for that character.

If we create characters that feel false, then the viewer can never really relate to them and it becomes impossible to get the audience to feel anything for that character. We've all seen movies where something terrible happens to the hero, and we should feel awful about it, but instead we're sneaking a peek at our phone to see how much longer until the movie's over.

Yes, the magical world Rowling created is amazing, but imagine if, instead of writing the Harry potter novels, Rowling had simply written a book describing the world of Hogwarts as though it were a catalog for prospective students. Or if she had written a book describing all the locales in Harry's world as though it were an Encyclopedia for wizards. There's no way that book would have ever become as popular as her novels. So the world itself--no matter how interesting--is not the core of the story. An imaginative world is not enough to enthrall an audience. Great characters are key.

The Star Wars universe is another example. There are many, many books describing all the planets and aliens of the Star Wars universe. I'm sure they're imaginative and interesting. But they aren't read an enjoyed nearly as much as the films are watched and enjoyed by audiences. Because the atlases and alien encyclopedias don't have the compelling characters that the films do.

Creating a fascinating world with lots of imagination is a great way to appeal to the intellect of an audience. The audience says to themselves "wow, that's clever." They can admire how interesting the world is, but they're not feeling anything yet. Once you create characters and give them human traits and foibles and problems, then you can appeal to the emotions of an audience, and that's when you can truly get them to invest in your movie and get them to feel joy or despair.

To sum up...don't get me wrong, great characters aren't the only thing that a story needs. Of course a great world for the story to take place in is important. A plot that makes sense is important as well. I just find that--in my opinion--many critics, bloggers and online posters focus too much on plot mechanics and visuals when they're judging a film. I think this happens because those are the most obvious and tangible elements when you're watching a film. Character is deeper and more difficult to talk about, and when it's done well, it can seem so natural that it seems effortless and obvious. But it's not.

Part of why I discuss this stuff all the time is because of my personal experience. People who write films and work in story tend to fall into the trap of focusing too much on plot and the mechanics of the story. We're guilty of the same thing that many critics and bloggers fall into. Plot elements are very tangible and easy to talk about. There's a logic and a concrete nature to the plot events of a story that make them easier to wrestle with and define than character.

Creating unique and interesting characters and digging deep into the psychology of those characters and figuring out why they are driven to do what they do is much, much more challenging. Creating characters that feel real and that are doing things out of real motivation is much harder than just creating a plot and manipulating characters into doing what they need to do to service the plot.

Chandler's plots don't always make a lot of sense (at least as I remember them). On his Wikipedia page, there's an excerpt from a reviewer that described his work as "rambling at best and incoherent at worst". That's about how I remember his books. But his well-defined characters and wonderful sense of atmosphere outshine the weakness of his plots and have kept his work popular with readers.

15 October 2016

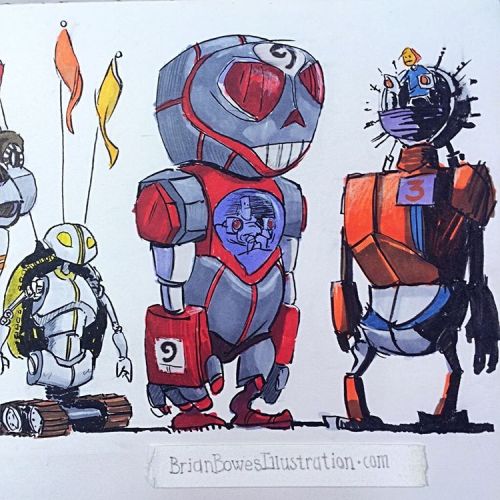

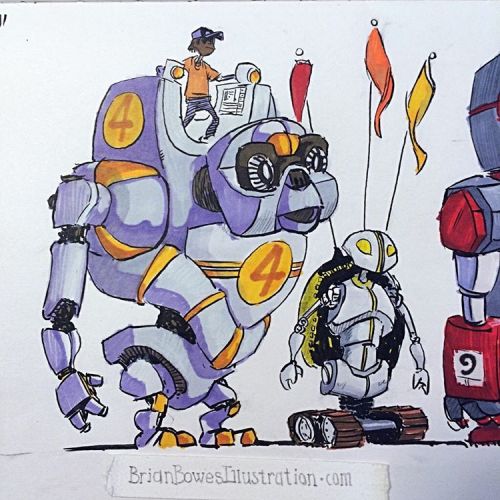

Some Shameless Self Promotion

Sometimes people ask me if I'll ever write a book about storyboarding. I would never want to do that...I enjoy sharing what little I know for free, and I've always felt that the whole point of having knowledge is to share it with others. So I'm glad people have found my posts helpful over the years. It's been very gratifying and you have all been a great audience.

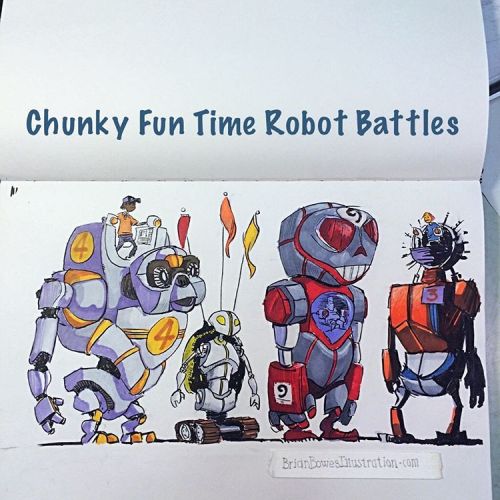

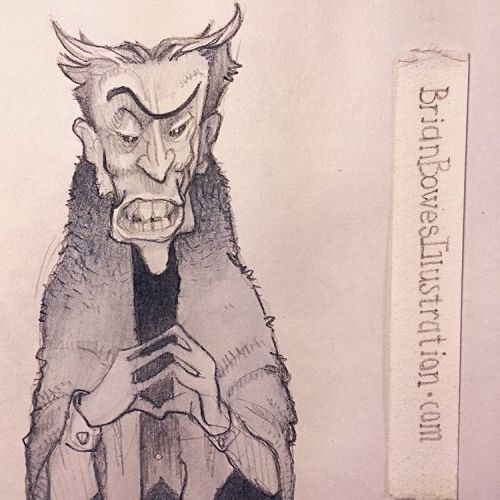

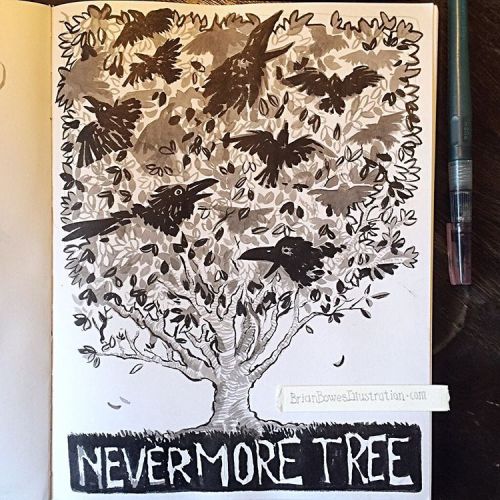

Over the past six years I have been working on a book, however...I've been writing and drawing a graphic novel that i'm planning on releasing next year, and now I need your help (don't worry, it's easy). In a shameless and transparent ploy to seem relevant and like I have an audience, I'm trying to get followers on social media. So if you wouldn't mind following me on Twitter, Tumblr and/or Instagram, I'd really, really appreciate it. I'm going to start posting a bunch of artwork from my graphic novel as well as other stuff I've done, so I promise to make it interesting.

Twitter link: https://twitter.com/Mark_D_Kennedy

Tumblr link: http://ift.tt/2dfxFW1

Instagram link: http://ift.tt/2dfzbY7

Thanks to everyone who still visits and thanks for all the nice things you've said over the years. I will continue to write posts here and I hope you'll continue to come!